To Live As Many Childhoods As Possible

Contemporary English-language picturebooks in India

India has the one of the highest reading rates of the world [1], one of the largest young populations, one of the fastest growing publishing industries [2], and one of the strongest linguistic bases in terms of English and local languages [3]. Yet there is a striking gap when one considers the data on the top thousand books sold in India annually: the list contains no independent, Indian books for children published in the last decade [4]. The overwhelming majority of the books sold are textbooks and self-help; Indian publishing has the smallest percentage of children’s books of any country surveyed by Nielsen Bookscan [5]; and any literature for young readers is dominated by British or American books and bestseller series, with the occasional RK Narayan or supposedly ‘pan-Indian’ [6] ancient folk tales and mythologies. Across the world, the representation of female characters and characters from minority or marginalised backgrounds is far too low and often peripheral [7][8].

To understand precisely why this is a problem we need to contextualise the Indian publishing industry and its young readership. The history of Indian literature for children begins with oral tales, followed by Christian missionary texts, British literature for the ideal colonial subject, Soviet books translated into Indian languages [9], bland post-Independence Indian publications that sought to avoid all mention of difference [10], and finally the emergence of independent, progressive Indian publishing houses in the late 1990s. Needless to say, if Indian children’s literature is to harness its ability to offer young Indian readers a mirror of their lives or a window into other worldviews [11], publishers have a vast array of childhoods in India alone to represent.

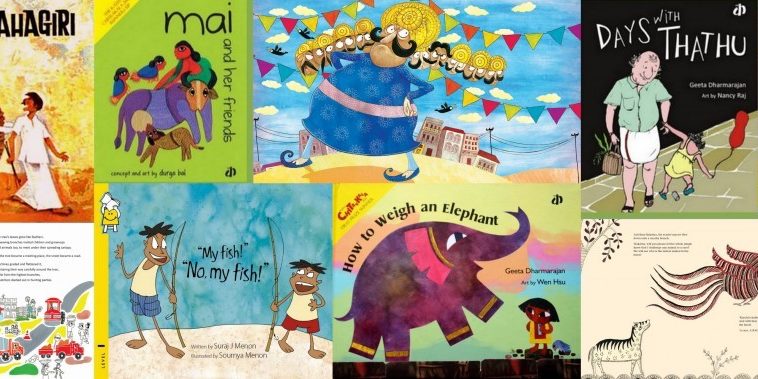

There is a handful of Indian publishers stepping up to the challenge, such as Tulika, Tara, Zubaan, and Little Latitude. On a surface level these books are led by characters with brown skin, surrounded by Indian landscapes, using Indian names, wearing Indian clothes and having Indian food. But exclusion or marginalisation do not operate solely from ‘West to East’, so to speak, and to reduce Indian characters to salwar kameezes, urban middle-class homes, dal and roti, and mangoes is to do a disservice to India’s youth. As V. Geetha of Tara Books writes, the implicit outcome of Western-dominated children’s literature is that Indian readers “grow up thinking that fun, adventure and fantasy can happen only elsewhere, in exotic foreign climes,” [12] and insufficiently attentive and diverse Indian books can have the same effect.

In light of this, certain publications merit greater attention, not only from publishers but equally from educators, parents, researchers, and the government. Progressive and inclusive children’s literature spans a range of formats, but of particular interest (though under-researched) is the unique dynamism that picturebooks have to offer. Far from being simply words with matching pictures, good picturebooks are built on a complex array of word-image interactions [13], and Indian art presents a plethora of opportunities to expand these. They are also faced with the challenge – or opportunity – of reconciling the global influences [14] and potentially growing need for individualisation in art [15], the economy, and education, with Indian values of ‘collectivity’ in knowledge, growth, and identities.

Hambreelmai’s Loom (2014) says on its cover that the folk tale is “retold” by Mamang Dai. The traditional conception of storytellers as keepers of a community’s collective memory [16] is echoed here with the implication that the story is on loan to the writer, owned by the Northeast Mishmi community as a whole, rather than individualised work credited to one person, as is often the case in classrooms. The illustrations by Kalyani Ganapathy turn the landscape on its head, as far as an urban reader is concerned, by using the ‘wrong’ colours and continually altering them. A closer look suggest that the birds, trees, fields, water and sky reflect the colours of the Mishmi weaves, just as the weaves’ patterns draw on the surrounding nature. The bamboo literally tumbles into line on the loom, while the patterns and colour schemes used lend the visuals a running, powerful rhythm that ties the book together and roots it in the small, remote mountainous community, offering readers a new conception of ‘reality’.

Instead of a traditional tale, Following My Paintbrush (2010) narrates the contemporary autobiographical story of Dulari Devi, a manual worker from Bihar who became a renowned Mithila painter. Artistically it ushers art into the readers’ lives, ready to be handled, scrutinised and explored as opposed to art as a “distant world” to be visited only occasionally (Corraini, 2007) [17]. The book draws out narratives otherwise absent from children’s literature [18], including realities of gender disparities, manual work in childhood, poverty and lack, and social stratifications. The framing of the book through the publisher’s writing, however, to some extent participates in positioning manual labour as inferior to Dulari Devi’s art, and in perpetuating the sense that marginalised communities need an ‘educated’, English-speaking counterpart in order for their voices to be heard.

In the urban Indian context, Gone Grandmother (2016) presents another female-dominated narrative, notable in relation to male-centric Indian joint families and death rituals. Alongside relatively generic markers of ‘Indianness’ [19] perhaps the most Indian aspect of the book is the integration of the protagonist Nina’s quest for understanding death, and the presence of her Nani throughout. Interspersed with Nina asking questions, drawing out fantastical possibilities, and pulling out general knowledge books to learn more are gossamer overlays of her Nani reading the same books to her, Nina helping her Nani up the stairs, and her memories of their activities complementing each other’s. Nina’s conclusion that Nani has become part of the stars, and the means by which she arrived at this conclusion – interweaving what Nani told her and what she read – are a reminder that collective and individual, local and global perspectives are not necessarily being torn apart, but rather forging “glocal” subjectivities [20] when given the space to do so, including in the pages of a book.

These books also all feature an aspect of religion or spirituality without foregrounding it, challenging the notion that these are relegated to the folk tales and mythologies that contemporary authors, educators, and parents are tiring of [21], and can instead form genuine parts of today’s diverse Indian narratives. It is easy for me to get lost in and excited by these books and the dozens of others like them, but they face several obstacles to obtaining a wide readership. On a logistical level, books can be too expensive or too difficult to distribute in much of India. Organisations such as Pratham are pioneering the use of digital books for India’s hardest to reach readers, work that will be crucial to future research in Indian children’s literature. As noted at the beginning of this article, the situation for urban, affluent readers is not much better: low print runs, short shelf lives, low commissions, a lack of public libraries and government support, vastly differing literacy rates, and a lack of reading culture in many schools and homes mean that although Indian children’s writers might have, according to author Anushka Ravishankar, “found their voice… often irreverent, funny, iconoclastic, and strong,” [22] children’s literature has a long way to go. It is little use opening a window or holding up a mirror if the many children, with their many childhoods, cannot or will not see into them.

Mira Manini Tiwari

(Mira is an Education Specialist at The Hearth Education Advisors)

21st October 2018

References:

1) NOP World Culture Score for Reading 2015. Retrieved 15 October, 2018, from http://chartsbin.com/view/32136

2) Subramaniam, M. (2013). Children’s book publishing in India. Publishing Research Quarterly, 29(1), 26-46. doi: 10.1007/s12109-012-9302-3.

3) Masani, Z. (2012, 27 November). English or Hinglish – which will India choose? BBC News. Retrieved 15 October, 2018, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20500312

4) Subramaniam, M. (2013). Children’s book publishing in India. Publishing Research Quarterly, 29(1), 26-46. doi: 10.1007/s12109-012-9302-3.

5) Nielsen Book Research: Data and insights for the book industry. (2017). Retrieved 15 October, 2018, from http://www.nielsenbookscan.com.au/uploads/Final%20Research%20Brochure_Digital(4).pdf

6) Shinde, S.P. (2016). The depiction of women in children’s literature in India. [PhD Thesis]. Savitribai Phule Pune University. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10603/126120.

7) Centre for Literacy in Primary Education. (2018). Reflecting Realities. Retrieved from https://clpe.org.uk/library-and-resources/research/reflecting-realities-survey-ethnic-representation-within-uk-children

8) Ferguson, D. (2018, January 21). Must monsters always be male? Huge gender bias revealed in children’s books. The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October, 2018, from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jan/21/childrens-books-sexism-monster-in-your-kids-book-is-male

9) Jankevičiūtė, G. & V. Geetha. (2017). Another history of the children’s picture book: from Soviet Lithuania to India. Chennai: Tara Books.

10) V. Geetha. (2010). The story of one publisher’s ‘new’ genre: the Tamil picturebook. Himāl Southasian. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from old.himalmag.com/component/content/article/162-between-literacy-and-reading.html

11) Nuttall, S. (2001). Reading, recognition and the postcolonial. Interventions, 3(3), 391-404. doi: 10.1080/713769062

12) V. Geetha. (2010). The story of one publisher’s ‘new’ genre: the Tamil picturebook. Himāl Southasian. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from old.himalmag.com/

13) Nikolajeva, M. and Scott, C. (2013). How picturebooks work. Retrieved from https://www.dawsonera.com/abstract/9780203960615

14) Kakar, S. & Kakar, K. (2009). The Indians: portrait of a people. Noida: Penguin.

15) Varma, R. (2013). Primitive Accumulation. Third Text, 27(6), 748-761. doi:10.1080/09528822.2013.857902

16) Ibid.

17) Quoted in Salisbury, M. & Styles, M. (2012). Children’s picturebooks: the art of visual storytelling. London: Laurence King.

18) Menon, R. & Rao, S. (2009). Text in Context: The culture and politics of stereotyping in children’s books. Wasafiri, 24 (4), pp. 16-22.

19) Superle, M. (2011). Contemporary English-language Indian children’s literature: representations of nation, culture, and the new Indian girl. New York: Routledge.

20) Gutierrez, A.K. (2013). Metamorphosis: the emergence of global subjectivities in the blend of global, local east, and west. In J. Stephens (Ed.), Subjectivity in Asian children’s literature: global theories and implications (pp. 19-42). London: Routledge.

21) Madhavan, M.R. (2017, October 7). Writers play hopscotch. The Mint. Retrieved October 8, 2017, from http://paper.livemint.com/epaper/viewer.aspx

22) Ibid.